The Business of Art: A Conversation with Dave Barton

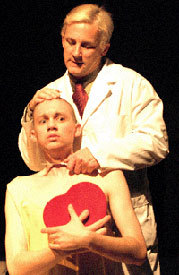

Performance photo of Boy Gets Girl (2005). (Photo: Jay Michael Fraley)

In a telling excerpt from a 1997 article on Rude Guerrilla Theater Company’s first production, In the House of the Lord, a slightly overwhelmed reviewer concludes that the play “oversteps the boundaries of good taste and is in truth a BLOOD BATH.” The play was written by Dave Barton, who is now Rude Guerrilla’s Artistic Director. Now in its eighth season, Rude Guerrilla has produced work by authors such as Sarah Kane, Samuel Beckett, and Ken Urban to occasionally baffled audiences in Santa Ana, CA. Boasting a track record that demonstrates a willingness—eagerness, even—to confront suicide, hedonistic drug use, porn, and deviant subcultures in the plays he produces and directs, Barton has helped establish Rude Guerrilla as one of the preeminent presenters of confrontational, exhilarating, dangerous, and emotionally exhausting theater in the country. He recently exchanged a series of emails with NYFA Current editor Nick Stillman.

Nick Stillman: Many of the plays Rude Guerrilla produces seem to flirt with emotional collapse; an uneventful blind date leads to a woman being stalked (Rebecca Gilman’s Boy Gets Girl), a trip to the moon becomes an exercise in extreme physical and existential isolation (Ken Jones’Darkside)…Is it purely coincidental that trauma fuels a good number of Rude Guerrilla-produced plays or is emotional rawness something you actively seek?

Dave Barton: The focus on that subject matter is partly out of existential concern—I’ve always been interested in the way that power shifts and moves within people and institutions. When something/someone gains or loses power, what is the process? Does it change the person for the good or play into the darkest parts of their personalities? Examining those moral and ethical issues fascinates me. Do we, as spiritual beings, have a place in the material world? Is that world something we create through our choices or is it something thrust upon us by fate or chance? Do we have any say in the matter?

As a longtime grassroots activist, I’m interested in how people lose or gain personal power, and, good anarchist that I am, I’m deeply concerned with the way institutions use power to keep themselves going and/or to crush individuals they feel threatened by. Since trauma/violence is often the result, both political concern and the opportunity to make people aware of what’s happening around them affect my choices in material. Figuring out/detailing how we short-circuit institutional power is dynamic to me as an individual as well as a director. Isn’t that what drama is anyway? Pondering a vision of someone or something changing for better or for worse?

In the work I’ve directed, awful, awful things happen to the people onstage. How they overcome it—if indeed they do—creates a really daring and exciting theater. I’m not interested in spooking people and leaving them confused and desperate, but I think I choose work that elevates hope over despair, but still acknowledges that despair exists, instead of trying to hide from it. I’m of the opinion that the walls we build around ourselves to keep out the harsher aspects of reality have a cocooning effect that keeps us warm in the arms of the status quo and prevents us from growing. To mix metaphors, we need a sledgehammer to smash down the wall, something that breaks through the pain and sadness. While that doesn’t always sell tickets, it can be very fulfilling artistically and personally.

Performance photo of

Cleansed (2004)

Written by Sarah Kane

(Photo: Dave Barton)

NS: Rude Guerrilla has produced what some might call “morally controversial” works by very challenging writers—Mark Ravenhill and the late Sarah Kane, just to name a few obvious examples. Is provocation something you seek from the plays you produce?

DB: I’m resistant to the idea of theater as something to be consumed and discarded. I’m much more interested in art that sticks around for a while. Provocation—political, sexual, intellectual—is the only kind of art with staying power. Theater shouldn’t be safe, and the main reason that it’s no longer the social force that it used to be is because it ended up playing to people’s worst instincts; it began to confirm our world view instead of challenging it, told jokes over communicating substance, became “entertainment” instead of education. A mirror isn’t any good if it just reflects the beautiful things.

As for shocking people, we get our share of gasps and hands over eyes, but the lobby is often filled afterwards with people talking, and there’s little better than that. I’m not so sure that people are as shocked by nudity, violence, or sexual things onstage. “Shock” is always in the eye of the beholder, and I think our audiences are generally smarter than the norm and see things the way we intend it—as a way to tell a fully engaged, complicated story—not just as a shock to the blue hairs. We occasionally get a negative response, but it’s almost always over onstage expressions of gay affection or sexuality, so there’s more than a hint of homophobia going on there. In the end, who has the time to listen to complaints about two women kissing? I think we’ve probably lost more patrons from envelope-pushing postcards than because of the shows themselves.

NS: Given your location in Orange County, CA—generally considered an overwhelmingly conservative part of the country—I’m curious to hear about how or if RG has integrated into and interacted with the community. Obviously, you haven’t tamed your aesthetic!

DB: OC was much more conservative when I was growing up. Its long line of asshole-ish Republican politicians—Bob Dornan, William Dannemeyer, Gil Ferguson, John Schmidt, to name just a few—is the main reason for that reputation, but they’re long gone. This isn’t to say that there aren’t holdovers. We had a handful of protestors when we produced the West Coast premiere of Corpus Christi. But even with the bomb threats, the clamor to shut us down from local churches, and the menacing phone calls, it was still only a handful.

Postcard for Penetrator (2003)

Written by Anthony Nielson

Designed by Jay Michael Fraley

I wish that theater was still a powerful enough medium that it routinely pissed people off, but, unfortunately, I think it’s a dead medium for the most part. While it has its moments where it looks like it’s going to rise up and stumble around like one of George Romero’s living dead, it’s usually because someone’s propping it up with donated labor or a hemorrhaging wallet. I know very few of us who wouldn’t jump at the chance to engage a bigger audience. Why play to 600 people over the course of a short theater run when you could play to thousands or millions by making a movie or television show?

We’re closely engaged with our community: For the first seven and a half years of our existence, we donated 10% of our profits from every show to charity—local or national—that had some tie-in with the play we were producing. Eventually, though, the nickels and dimes we were handing out seemed inconsequential when we had one-night readings or fundraisers for specific charities and donated an entire night’s receipts. Those seemed to drum up larger houses and more money through the accompanying press. We’re also close friends with the local chapter of The Catholic Worker, donating money, food, clothing, free tickets, and volunteering time with them.

NS: What do you look for in a play to produce? Could you share an example of a recent play you read that just totally blew you away?

DB: I’m attracted to smart, literate work with a sense of humor, unblinking honesty, social engagement, and that’s unafraid to be unusual, even confrontational. It can be drama, comedy, tragedy, avant-garde, classic, or contemporary—if it possesses the qualities I just mentioned, I’ll probably be interested in producing it.

The two plays I read recently that come to mind, both of which I’m directing within the next year:

1) The Sacred Geometry of S&M Porn by Johnna Adams. It’s a very, very black comedy about an abused teenage boy who finds a stack of dirty magazines and forms his own religion. It has mass media, puppets, politics, a critique of televangelism and brain-washing cults, orgies, mass suicide, gunplay, sex, equal opportunity nudity, Mike Wallace, resurrected bodies, an assassination…everything I could ask for in a play!

2) Mysterious Skin by Prince Gomolvilas, adapted from the terrific novel by Scott Heim. The novel was recently made into a very good indie film, so I was hesitant to read it, but it just jumps off the page. It examines the way two young men deal with sexual molestation—one thinks he’s been abducted by aliens and the other becomes cold-hearted and promiscuous. When they meet again after many years, the truth about their situations unravels itself in a very sad, deeply compassionate way. Its final image—two people holding each other in the face of encroaching darkness—is my favorite image in film and television. To my bleak but hopeful way of thinking, it says it all.

For more information on Dave Barton and Rude Guerrilla Theater Company, visit:

www.rudeguerrilla.org